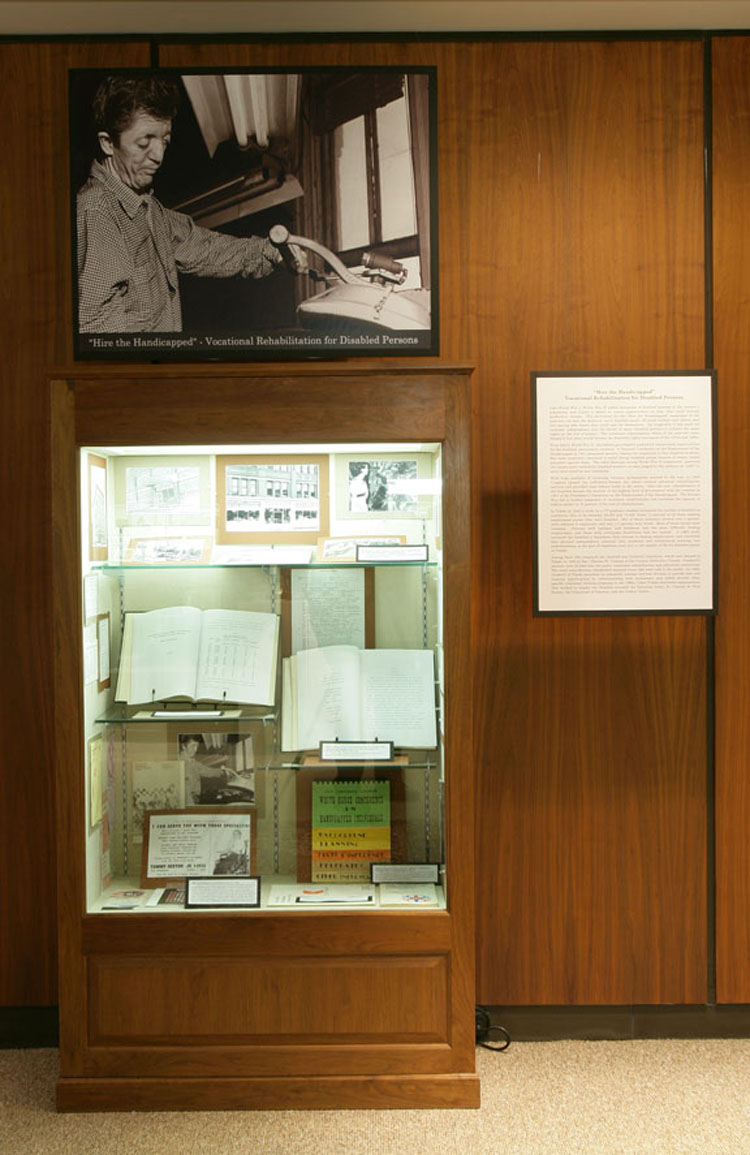

“Hire the Handicapped”—Vocational Rehabilitation for Disabled Persons.

Like World War I, World War II added thousands of disabled persons to the country’s population and fueled a desire to create opportunities so that they could become productive citizens. The motivation for the “Hire the Handicapped” campaigns of the post-war era was the desire to move disabled people off social welfare and charity and into paying jobs where they could care for themselves. An outgrowth of this push for economic independence was the desire of many disabled persons to achieve the same rights as the rest of society. The vocational rehabilitation efforts of the post-war years helped to fuel what would become the disability rights movement of the 1970s and 1980s.

Even before World War II, the federal government pushed for employment opportunities for the disabled, particularly veterans. A National Conference on the Employment of the Handicapped in 1941 presented positive reasons for employers to hire disabled workers. But most employers continued to resist hiring disabled people because of deeply rooted prejudice against them. The labor shortage during World War II temporarily improved the employment outlook for disabled workers, as men judged by the military as “unfit” to serve were hired by war industries.

With huge numbers of returning veterans permanently scarred by the war, in 1943 Congress passed the LaFollette-Barden Act which created advanced rehabilitation services and provided some federal funds to the states. After the war, rehabilitation of the disabled became the interest of the highest level of government with the creation in 1947 of the President’s Committee on the Employment of the Handicapped. The Korean War led to further expansion of vocational rehabilitation and increased the amount of federal money to 75 percent of the cost of rehabilitation.

In Toledo in 1948, a study by a UT graduate student estimated the number of disabled in northwest Ohio to be between 38,000 and 75,000. Some 12 percent of all those seeking employment across Ohio were disabled. But of these, statistics showed only 4 percent were referred to employers, and only 1.7 percent were hired. Most of those placed were veterans. Persons with epilepsy and blindness had the most difficulty finding employment, and those with orthopedic disabilities had the easiest. A 1962 study surveyed the disabled to determine their success in finding employment, and concluded that physical independence, parental care, academic and occupational training, and understanding on the part of employers were key to the quality of life for disabled people in Toledo.

Among those who employed the disabled was Goodwill Industries, which was started in Toledo in 1933 by Rev. Charles W. Graham of the Central Methodist Church. Goodwill’s services were divided into two parts: vocational rehabilitation and industrial contracting. The retail sales division refurbished donated items that were sold to the public. In 1950, Goodwill of Toledo launched its industrial contract services division to provide jobs and training opportunities by subcontracting with businesses, and added several other specific vocational training programs in the 1960s. Other Toledo charitable organizations that worked to employ the disabled included the Salvation Army, St. Vincent de Paul Society, the Volunteers of America, and the Conlon Center.